- Home

- Taxonomy

- Term

- PAGES Magazine Articles

PAGES Magazine articles

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

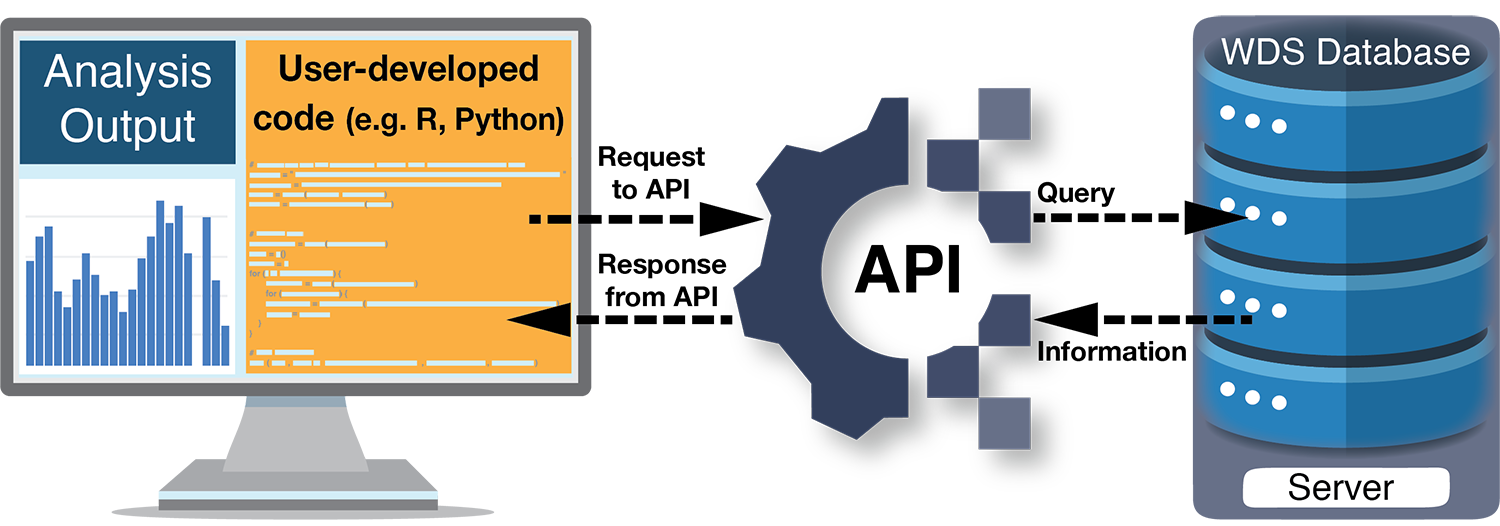

As the spatial and temporal resolution of scientific datasets and the culture of data sharing grow, more data on past global changes are now available than ever before. Efficiently discovering, downloading, and integrating data into analyses is critical for making full use of this surge of information. Researchers have long used Graphical User Interfaces1, or GUIs, to manually search and download data, but Application Programming Interfaces, or APIs, can handle these tasks in a more automated fashion. In fact, APIs are the behind-the-scenes conduit for many different types of information we use every day, from weather forecasts within smartphone apps to flight schedules aggregated on travel websites.

APIs are the technological backbone that let two computer programs communicate over the internet. Each API defines a set of rules that specify the parameters by which requests (or "calls") can be made, as well as the format of the computer-readable information that is provided in response. World Data System repositories such as the World Data Service for Paleoclimatology (WDS-Paleo)2, PANGAEA3, and Neotoma4 provide APIs, as do other data and information sources such as publishers (e.g. Springer, Wiley), publication databases (e.g. CrossRef, Web of Science), domain-specific databases (e.g. Global Biodiversity Information Facility), and analysis tools (e.g. ArcGIS).

A request to an API is usually written in the form of a specially-formatted web address, or Uniform Resource Locator (URL). Scientists can call an API by simply entering such a URL into their web browser or by incorporating calls to an API in data analysis code. These new capabilities open more automated ways of first finding and accessing information, and then integrating information, both from different sources, and with different analysis tools.

The ability to discover and download information programmatically via an API, as opposed to manually through a GUI, increases efficiency and diminishes the possibility for human error. For example, APIs make it easier to repeat a search (perhaps to find newly archived datasets or updates to existing datasets) or to gather information quickly for initial data exploration (perhaps to identify certain geographical areas or parameter types with sufficient amounts of data for an analysis). APIs can also make it more efficient to search multiple data providers. While requests must be structured to match the requirements of a specific API, they can be a useful way to locate data across several repositories. In fact, the federated data search provided by the WDS-Paleo API uses the Neotoma API to retrieve information about datasets.

API requests can be integrated with many programming languages (e.g. Python, R, MatLab), effectively creating a pipeline of data to tools for analysis. For example, functionality to access data from the PANGAEA, and Neotoma data repositories via their APIs exists in some Python5 and R6,7 packages (e.g. Goring et al. 2015) and the WDS-Paleo also provides example API requests in these languages8. Incorporating API requests into a scientific workflow promotes reproducibility and repeatability of research. Encoding all steps of the workflow from data discovery and download to processing and analysis provides complete documentation of the research methods, including the criteria used to select datasets. Some APIs also perform analysis directly: for example in the geospatial ecosystem, ArcGIS APIs9 and Open Geospatial Consortium APIs10 perform geospatial analysis, including image analysis and feature classification.

While APIs provide the ability to access formatted information directly from computer systems of authoritative sources, thereby streamlining data access and analysis, there are still some obstacles to integrating data from different repositories or sources seamlessly (e.g. EarthLife Consortium API11; Uhen et al. 2021). For example, interoperability and reusability of paleoenvironmental data also require enhanced common standards and workflows for metadata and data reporting (Bothe et al. 2021; Khider et al. 2019; Morrill et al. 2021; Williams et al. 2018). These improvements, in concert with technological advances such as APIs, will accelerate discovery from the many decades of data collection by the paleo community.

affiliationS

1National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Boulder, CO, and Asheville, NC, USA

2Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado Boulder, CO, USA

3Riverside Technology, Inc, Fort Collins, CO, USA

contact

Wendy Gross: paleo noaa.gov

noaa.gov

references

Bothe O et al. (2021) PAGES Mag 29: 59

Goring S et al. (2015) Open Quat 1: Art 2

Khider D et al. (2019) Paleoceanogr Paleoclimatol 34: 1570-1596

Morrill C et al. (2021) Paleoceanogr Paleoclimatol 36: e2020PA004193

Uhen MD et al. (2021) Front Biogeogr 13: e50711

Williams J et al. (2018) PAGES Mag 26: 50-51

Links

1For example: ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search, pangaea.de, apps.neotomadb.org/explorer

2ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search/api

3ws.pangaea.de

4api.neotomadb.org/api-docs

5github.com/pangaea-data-publisher/pangaeapy

6docs.ropensci.org/pangaear

7cran.r-project.org/web/packages/neotoma

8ncei.noaa.gov/access/paleo-search/api#examples

9developers.arcgis.com/rest

10ogc.org/resource/demos-archive

11earthlifeconsortium.org

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

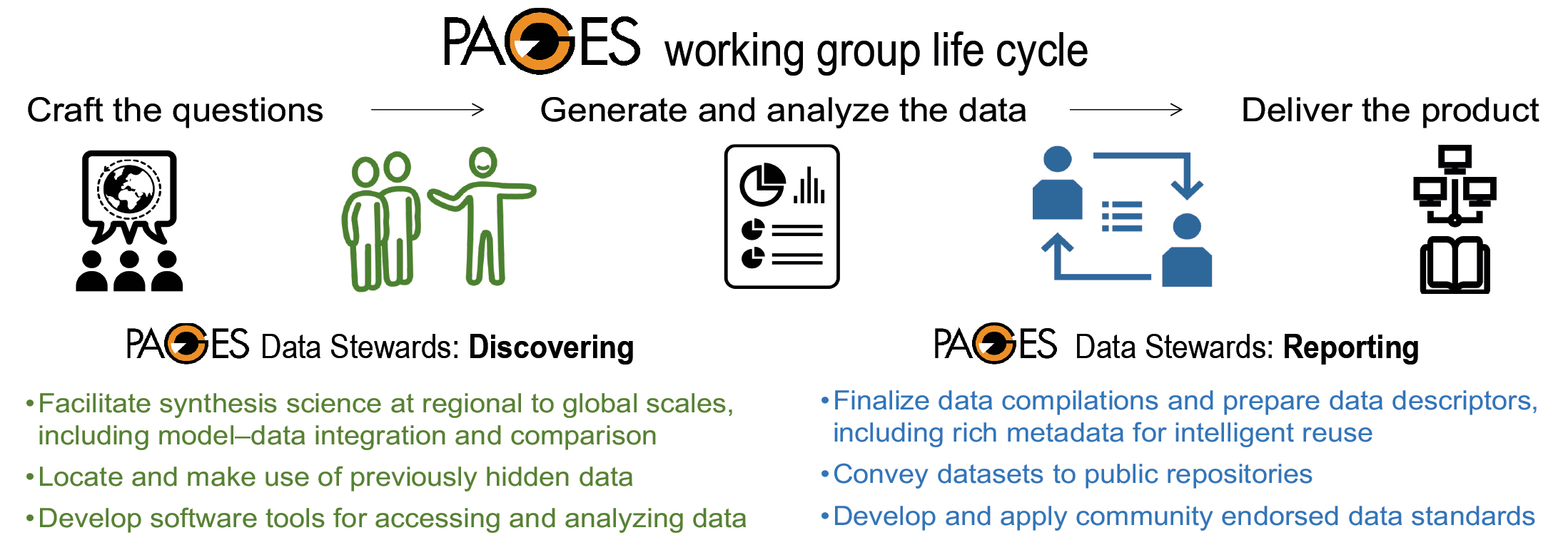

Eleven new PAGES-funded Data Stewards are helping PAGES working groups to discover, analyze, and curate community data resources.

Professional scientific organizations are playing an increasingly important role in motivating the cultural shift toward FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data practices (PAGES Scientific Steering Committee 2018). PAGES now offers its working groups financial support to help develop open data resources that facilitate high-impact global change research. The first nine PAGES Data Steward Scholarships are now underway. Stipends averaging USD 14,400, and ranging up to USD 20,000, recognize and reward early-career researchers and established specialists for their valued efforts to compile and curate data products for the long-term benefit of the global paleoscience community.

These data stewards are serving key roles in the life cycle of PAGES working groups, both in the data-discovery and data-reporting stages (Fig. 1). They are helping to accelerate the rate at which past-global-change data are entering the public domain. They are gathering the essential metadata needed for intelligent data reuse, and are formatting the datasets so they are amenable to analysis by open-source code. PAGES data stewards are implementing practices that model and promote FAIR data principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016), while making use of, and reducing loss of, valuable data (Kaufman and PAGES 2k special-issue editorial team 2018). Their contribution as curators of community data resources will extend well beyond the lifetime of a working group (Williams et al. 2018).

|

|

Figure 1: Data stewards are supported financially by PAGES to serve key roles in the life cycle of PAGES working groups, both in the data-discovery and data-reporting stages. |

PAGES-funded data stewards are helping PAGES working groups to achieve their goals in a variety of ways. Specifically:

C-PEAT (Carbon in Peat on Earth through Time) held a series of "data-collection happy hours" to gather contributions of peat-based proxy records from around the world. The data and essential metadata are being standardized for use in ecosystem models to understand carbon and water cycling.

pastglobalchanges.org/c-peat/data

C-SIDE (Cycles of Sea-Ice Dynamics in the Earth system) has compiled a dataset of sea-ice records from the Southern Ocean over the last glacial-interglacial cycle and is preparing a data descriptor for publication.

pastglobalchanges.org/c-side/data

OC3 (Ocean Circulation and Carbon Cycling) is building on its World Atlas of late Quaternary foraminiferal oxygen and carbon isotopes by generating quality-controlled age models for the highest resolution records, with the goal of resolving rapid changes during the last deglacial transition.

pastglobalchanges.org/oc3/data

2k Network is assembling all existing 2k datasets, including those featuring paleo temperature, moisture and isotopic records of the Common Era, to improve their accessibility and interoperability. They plan to develop a one-stop portal that describes the datasets in multiple languages. Within the 2k Network, CoralHydro2k has added 41 seawater oxygen-isotope records to its data compilation. Nearly half of these were previously "hidden" behind paywalls and in grey literature. These data will help calibrate marine carbonate proxies and improve models of ocean-atmosphere interactions. CLIVASH2k's community-wide data call netted 110 new sodium and sulphate datasets from Antarctic ice cores. The data were received in various forms and are being compiled into a uniform format, while fleshing out missing metadata. The data will be used to reconstruct Antarctic atmospheric circulation and surface mass balance over the past 2000 years.

pastglobalchanges.org/2k/data

PALSEA (PALeo constraints on SEA level rise) is merging the recently published Holocene sea-level database with the existing world atlas of last interglacial sea-level indicators. The group is planning to improve the online database interface to help address questions about the drivers of sea-level change at local to global scales.

pastglobalchanges.org/palsea/data

PEOPLE 3000 (PalEOclimate and PeopLing of the Earth) is expanding its global compilation of archaeological radiocarbon data to support research on human paleodemography.

pastglobalchanges.org/people-3000/data

SISAL (Speleothem Isotope Synthesis and AnaLysis) is updating its well-established database to include speleothem trace-element time series. It plans to develop a computer app to enhance database accessibility. pastglobalchanges.org/sisal/data

Any member of a PAGES working group can apply for a Data Steward Scholarship. Contact your working group leaders. For more information see the PAGES website: pastglobalchanges.org/dss

affiliation

Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, USA

contact

Darrell Kaufman: Darrell.Kaufman nau.edu

nau.edu

references

Kaufman DS, PAGES 2k special-issue editorial team (2018) Clim Past 14: 593-600

PAGES Scientific Steering Committee (2018) PAGES Mag 26: 48

Publications

Land-cover and land-use change through the Holocene: Wrapping up the PAGES LandCover6k working group

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

Austin "Chad" Hill![]() 1, N. Whitehouse2, M. Madella3, K.D. Morrison1 and M.-J. Gaillard4

1, N. Whitehouse2, M. Madella3, K.D. Morrison1 and M.-J. Gaillard4

Online, 2 - 4 December 2021

The PAGES LandCover6k working group (Gaillard et al. 2015; pastglobalchanges.org/landcover6k) met in December 2021, via Zoom, for the final scheduled conference on the progress of the group (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/26936). Thirty-six authors presented 29 papers, over four sessions, on regional reconstructions of land cover and land use, as well as the related topics of synthesizing and publishing the output of the project and collaborating with climate modelers. The meeting, originally planned to be held in person in Philadelphia in 2020, was moved online due to ongoing Covid concerns. While it was disappointing not to be able to host our colleagues in-person, the online format allowed many people to present, and a wider audience to attend, than might have been possible otherwise.

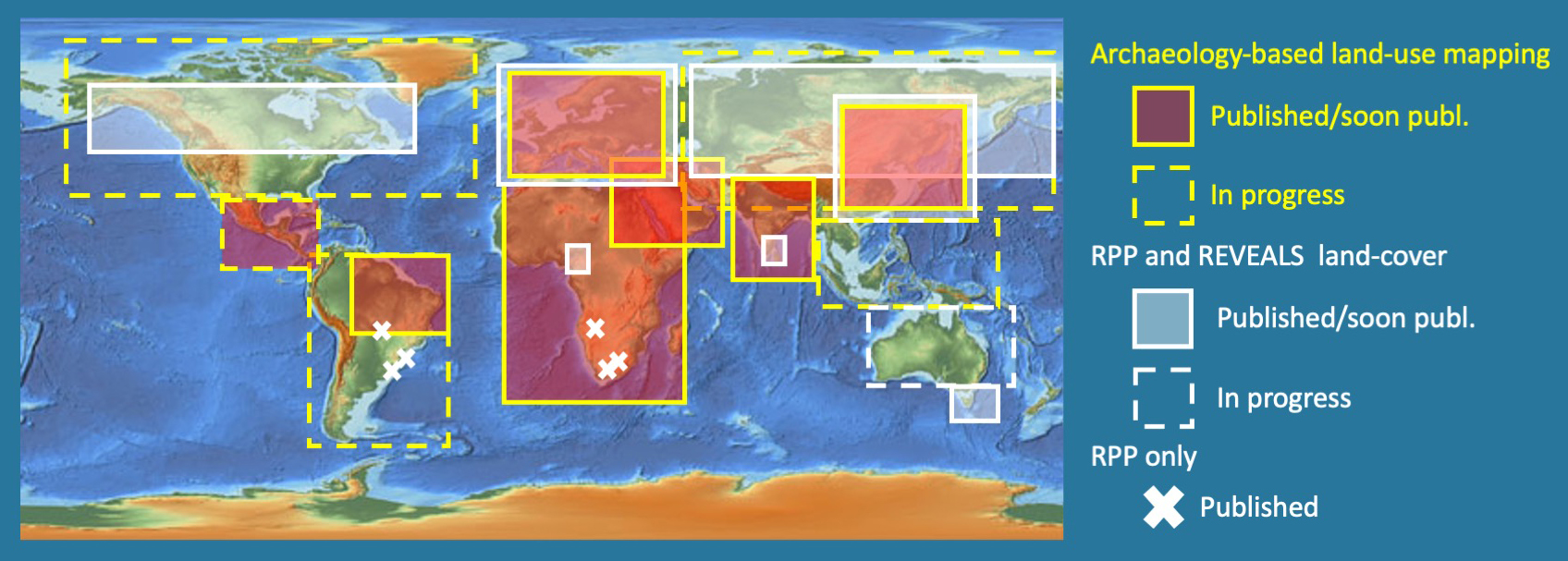

Global overview and regional progress

A global overview of the progress made during the working group's lifetime was provided by Marie-José Gaillard, Kathy Morrison, Marco Madella, and Nicki Whitehouse. Significant headway has been made with the publication of both land-cover and land-use reconstructions (e.g. Gaillard et al. 2018, Morrison et al. 2021, Githumbi et al. 2022) for the Holocene. These reconstructions are designed to help improve Anthropogenic Land-Cover Change (ALCC) scenarios such as HYDE 3.2 and achieve paleoclimate model simulation experiments (e.g. Strandberg et al. 2022). Four sessions were divided by global region, providing regional subgroups with the opportunity to provide updates on the progress of past land-use and land-cover change mapping. In a few regions, including Europe, China, and the Near East, data analysis is nearly complete for both pollen-based reconstructions of past land cover and archaeological data-based land-use maps. In many other regions, work has progressed further for either land cover or land use. For land-use reconstructions, much of the discussion revolved around the different approaches that have developed for different regions, especially methods of interpolating archaeological site data to the regional scale, based on the differences in the availability of published site data and accurate 14C dates.

|

|

Figure 1: Progress of PAGES LandCover6k publications by region (image credit: K.D. Morrison, M.-J. Gaillard). |

Integrating land cover and land use

Two key recurring topics discussed throughout the conference were the challenge of incorporating regional land-use data into a final global database so that it can be useful to climate modelers, and the challenge of integrating land-use and land-cover data. One important ongoing effort to do this comes in the form of a recently awarded PAGES data stewardship scholarship. This will help fund the long-term curation of pollen-based REVEALS land-cover reconstructions, gridded at 1º x 1º over 25 time windows throughout the Holocene (e.g. Githumbi et al. 2022), a new global historical Per Capita Land-Use (PCLU) database, and regional historic land-use data using the LandCover6k classification system gridded at 8km x 8km (Morrison et al. 2021). The REVEALS reconstructions for Europe, first (Trondman et al. 2015; Marquer et al. 2014) and second (Githumbi et al. 2022) generations, are already archived in PANGAEA (Gaillard 2019; Marquer et al. 2019, and Fyfe et al. 2021), as well as the land-use map for the Middle-East at 6 kyr BP (Hammer 2020).

The future of LandCover6k

This was the final conference of the PAGES LandCover6k working group in its current incarnation. However, a lively thread running through the meeting was the ongoing nature of the work, and the need for the work to continue. Discussions continue about how to finish individual publications, how collaborations between land-use and land-cover researchers will endure, and how the results from regional land-use work will be brought together into the final global database, as well as new research directions.

One important change, as LandCover6k transitions to the next stage, will be in leadership. Marie-José Gaillard has recently retired and will step down as group coordinator for future iterations of the project. We thank Marie-José for her tireless work inspiring, organizing, and shepherding the group over the last seven years. We also wish to thank all colleagues worldwide who coordinated subgroups, provided and/or collected data, contributed to land-use and land-cover reconstructions, and worked on the publication of datasets and results. Last but not least, we are grateful to all members of the core group (Victor Brovkin, Jane Bunting, Anne Dallmeyer, Erle Ellis, Jed Kaplan, Kees Klein Goldewijk, Sandy Harrison, Boris Vannière, and Peter Verburg) and the rest of the coordinating group, in addition to the authors (Jennifer Bates, Oliver Boles, Andria Dawson, Esther Githumbi, Emily Hammer, Sandy Harrison, Furong Li, Stefania Merlo, and Marc Vander Linden) for the valuable discussions and exchanges of ideas during numerous meetings over the years.

affiliationS

1Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

2School of the Humanities, University of Glasgow, UK

3ICREA - Department of Humanities, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

4Department of Biology & Environmental Science, Linnaeus University, Kalmar, Sweden

contact

Chad Hill: chadhill sas.upenn.edu

sas.upenn.edu

references

Fyfe RM et al. (2021) PANGAEA, doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.937075

Gaillard M-J et al. (2015) PAGES Mag 23: 38-39

Gaillard M-J et al. (2018) PAGES Mag 26: 3

Gaillard M-J (2019) PANGAEA, doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.897303

Githumbi E et al. (2022) Earth Syst Sci Data, doi:10.5194/essd-2021-269

Hammer E (2020) PANGAEA, doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.922243

Marquer L et al. (2014) Quat Sci Rev 90: 199-216

Marquer L et al. (2019) PANGAEA, doi:10.1594/PANGAEA.900966

Morrison KD et al. (2021) PLoS One 16: e0246662

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

Julie Loisel![]() 1 and Angela Gallego-Sala

1 and Angela Gallego-Sala![]() 2

2

United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), Glasgow, Scotland, 31 October - 12 November 2021

On Friday, 5 November 2021, the C-PEAT working group, in collaboration with PAGES and Future Earth, presented an exhibit during the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland. Professors Julie Loisel and Angela Gallego-Sala (the group co-leads) gave the lecture "Getting to know peatlands, the largest natural land carbon stores on Earth", presenting updated knowledge on the global peatland carbon stocks, peatlands' sensitivity to past and future climate change, and the role of peatlands as natural climate solutions.

Peatland Pavilion

The C-PEAT lecture was hosted by the Peatland Pavilion (wedocs.unep.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/37197/COP26GP.pdf) that was organized by UNEP's Global Peatlands Initiative. The Pavilion's exhibit hall was packed with art pieces and artefacts from peatlands. The agenda was fully booked with panels and lectures for the entirety of the two-week conference. At the Pavilion, scientists and practitioners drew attention to the importance of peatlands in climate change mitigation, mainly via peatland restoration and protection. That peatlands are considered important enough to be granted a Pavilion at a COP meeting speaks volumes in itself. Their role as global cooling agents is now widely accepted; likewise, the threats these natural carbon sinks face from climate and land-use changes are also well known. Protecting peatlands has been described as "one of the most important tasks of this decade".

|

|

Figure 1: Artistic rendition of a peatland landscape throughout its development. These six posters were presented as part of the Peatland Pavilion exhibit at COP26. Drawings by Patrick Campbell. High-resolution images available for download at julieloisel.com/cpeat. |

C-PEAT contributions

The C-PEAT group contributed an interactive peatland map (julieloisel.com/cpeat) that showcases > 75 sites from 20 countries that have been studied by the C-PEAT scientific community. The map was combined with a library of peat cores that were displayed at the Peatland Pavilion. This part of the exhibit helped attendees—both online and in-person—to appreciate where peatlands are located and what peat looks like. The map was created by Sedrick Utt, an undergraduate student researcher in the Department of Geography at Texas A&M University, USA; his work was funded by PAGES.

In collaboration with Patrick Campbell, who is an artist and peatland enthusiast, we also presented six drawings of peatland landscapes (Fig. 1), each representing a different stage in a peatland's development. For each portrait, different proxies were also drawn to represent the role of peatlands as natural archives; short texts explained how paleoecologists can reconstruct past environments and infer past landscapes from said proxies.

The talk (youtube.com/watch?v=Q4vRIefClZc) was aimed at a broad audience of informed stakeholders, practitioners, and scientists. Topics covered included: "How do we quantify the global peatland carbon stock?", "How does climate affect the peatland carbon sink?", "How will peatland extent change with warming?", and "Future research directions for C-PEAT". A PDF version of the slideshow is available (drive.google.com/file/d/1HnLJAwmJ9G3f-lmlGhC5FCXM_fwCqW4o/view); everyone is welcome to use the slides.

Achievements and concluding remarks

The Peatland Pavilion provided clear messages about the importance of restoring degraded peatlands—namely through rewetting—and protecting pristine ones. The work of peatlands as natural solutions to mitigate climate change sits well within COP26's "Glasgow Leaders' Declaration on Forests and Land Use", which was signed by more than 140 countries promising to work collectively to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030. This pledge should be beneficial for peatlands; our interpretation is that the commitment will encompass efforts to help halt the further degradation of peatlands worldwide. In addition, countries such as Chile, Peru, Indonesia, and the DRC included peatlands in their national pledges under the Paris Agreement—known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)—for the first time. Lastly, multilateral development banks (MDBs) now consider both the extraction of peat and electricity generation from peat to be universally not aligned with the Paris goals. This is important because it may change how investments are made in terms of what is considered sustainable development, which should include the avoided conversion of peatlands.

affiliationS

1Department of Geography, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA

2Department of Geography, University of Exeter, UK

contact

Julie Loisel: julieloisel tamu.edu

tamu.edu

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

Florian Adolphi![]() 1, C. Barbante

1, C. Barbante![]() 2,3, P. Bohleber

2,3, P. Bohleber![]() 3, G. Mollenhauer

3, G. Mollenhauer![]() 1, T. Tesi

1, T. Tesi![]() 2 and F. Wilhelms

2 and F. Wilhelms![]() 1

1

Bologna and Venice, Italy, 6-8 October 2021

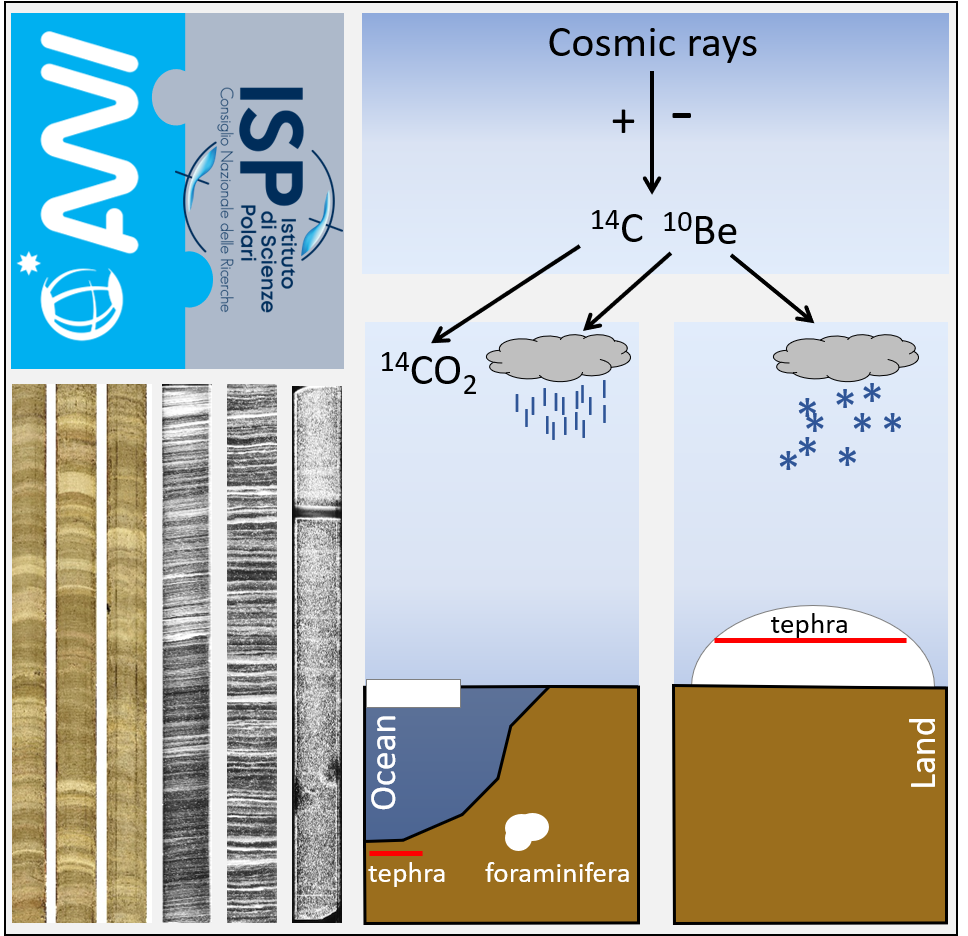

The new international collaborative project called PAIGE (Chronologies for Polar Paleoclimate Archives - Italian-German Partnership) is funded by the Helmholtz Association and aims to strengthen collaborative research between the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) and the Italian Institute of Polar Sciences of the National Research Council of Italy (ISP-CNR). The project's key theme revolves around the ambitious goal of linking chronologies for paleoclimate archives from ice cores and sediment cores.

At the beginning of the PAIGE project, an international workshop on chronology of high-latitude paleoclimate archives was held in Bologna and Venice, Italy, in October 2021. The aim of the conference was to identify the state of the art but also the main gaps of knowledge regarding chronologies and synchronization of polar paleoclimate archives. The conference was held in a hybrid format, allowing for in-person and online attendance. Participants included students and early-career researchers, as well as senior scientists. The plenary session featured 11 invited keynotes followed by discussion and a final wrap-up session each day.

During the conference, a common theme developed around the potential and limitations of linking chronologies from different archives as well as hemispheres. New approaches and techniques for achieving precise chronological control were presented. A special role in this context is played by identifying traces of volcanic eruptions through their chemical signature, as well as tephra deposits. On this topic, Michael Sigl (University of Bern, Switzerland) presented the potential of volcanic signals to improve ice-core dating during the Holocene, as well as to investigate the short-term climatic and societal impact of volcanic eruptions. His talk was complemented by Anders Svensson's (University of Copenhagen, Denmark) presentation on bi-polar ice-core synchronization by means of ice-core sulfate records over the last glacial period. Allessio Di Roberto (INGV, Pisa, Italy) then discussed how to bridge the gap to the marine sector by using tephra particles found in ice cores and sediments. Another powerful synchronization tool is cosmogenic radionuclides such as 10Be; Raimund Muscheler (Lund University, Sweden) presented how ice-core 10Be and 36Cl records can be used to detect changes in the cosmic ray flux, while Martin Frank (GEOMAR, Germany) illustrated the potential and challenges of using 10Be to date marine sediments.

Felix Ng (Sheffield University, UK) showed recent advances in the model treatment of impurity diffusion in ice cores, which is directly relevant to the interpretation not only of volcanic peaks, but also of cosmogenic radionuclides found at greater depths. In addition, Francesco Muschitiello (University of Cambridge, UK) elaborated how to use advanced probabilistic methods to synchronize environmental archives based on their proxy records. Besides synchronization, another focus was on the absolute dating of ice cores and sediments using radiometric methods. Florian Ritterbusch (University of Science and Technology of China) discussed recent advances in using radiogenic noble gas isotopes of Ar and Kr for absolute ice-core dating, with particular examples of how this novel dating technique by atom trace trap analysis can constrain existing chronologies. Walter Geibert (AWI, Germany) showed new approaches of using U-series isotopes to obtain high-resolution chronologies in marine sediments back to ∼450 kyr ago. For younger sediments, radiocarbon is the most commonly employed dating method and Claire Waelbroeck (LSCE, France) and Jutta Wollenburg (AWI) discussed challenges related to the marine reservoir age and post-depositional alterations of carbonate shells, respectively.

Inspired by two days of presentations and discussions, the third day of the workshop was dedicated to ongoing work within PAIGE: in Bologna, early-career researchers working on permafrost dynamics presented and discussed their results and explored options for increased collaboration and exchange between the institutes. In Venice, a subgroup intensified the discussion on obtaining high-resolution impurity data from ice cores, specifically with laser ablation inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICPMS).

Ultimately, the outcome of the workshop highlighted not only the importance of linking chronologies from marine and ice archives, but also the ambitious nature of such an endeavor. No single dating method is likely to deliver this breakthrough, but the path forward lies in a multi-disciplinary combination of high-resolution stratigraphic dating methods in concert with absolute age constraints from radiometric techniques. Accordingly, it will be crucial to have marine and ice-core experts continue and intensify their inter-disciplinary dialogue. Facilitating this exchange will be a lasting added value of the PAIGE project to the two scientific communities. People interested in learning more about the project and upcoming activities are invited to contact Florian.Adolphi awi.de or Pascal.Bohleber

awi.de or Pascal.Bohleber unive.it.

unive.it.

affiliationS

1Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI), Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany

2Institute of Polar Sciences – National Research Council of Italy

3Ca'Foscari University of Venice, Italy

contact

Florian Adolphi: florian.adolphi awi.de

awi.de

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

Marcel Mindrescu1,2 and Ionela Grădinaru2,3

Carlibaba (Fluturica), Suceava County, Romania, 5-9 October 2021

Central Eastern Europe (CEE) and the Carpathian-Balkan region (CBR) are of particular interest for paleoscientific investigations for several reasons. Firstly, the location at the contact/transition between the smaller landmass of Western Europe, where the climate is largely dictated by North Atlantic air masses, and the large continental mass extending beyond the Carpathian range, which falls under the influence of excessive continental climate, turns the Carpathian and Balkan ranges into a boundary between the two major climatic influences of the European continent. Secondly, the significant elevation range peaking at 2925 m asl favors the capture of regional and continental-scale climatic signals and determines a strong vegetation gradient. Thirdly, the diversity of landforms—including those with glacial, periglacial, or paraglacial origins; underground cavities (caves and shafts; see Fig. 1); lakes; and peatbogs—provide opportunities for paleoclimate and paleoenvironment reconstructions.

Until recently (i.e. before the 2010s), CEE was unrepresented in large data reviews that discussed well-dated, high-resolution investigations of past climate and environmental conditions and studies on human impact on the local and regional environment. However, as new paleoclimatic records are continuously being generated, this area is no longer a blank spot in regional and continental-scale climate reconstructions. The significant advancement of paleoscientific research in this region is ascribed to recent scientific efforts, including five regionally relevant meetings focused on climate changes and paleoclimate reconstructions organized in the past decade in Romania with the continued support of PAGES, and the establishment of a dedicated working group, the Carpathian Climate and Environment Working Group CarpClim (pastglobalchanges.org/science/end-aff/carpclim).

The Carpathian-Balkan Paleoscience Workshop (CBPW) 2021 (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/26996) was an initiative of the Geoconcept Association of Applied Geography (geoconcept.ro) supported by PAGES and endorsed by the Geography Department of the University of Suceava in Romania and other research and academic institutions and structures. The proceedings of the workshop were held in a traditional Bukovinian village located on a highland plateau (ca. 1250 m asl) in the Northern Romanian Carpathian as a "green scientific event" committed to respecting public health safety requirements and providing support for local communities, while maintaining a low carbon footprint.

|

|

Figure 1: Karst lithology and caves in Romania (Bădescu and Tîrlă 2020). Information about 12,300 caves is archived at the "Emil Racoviță" Speleological Institute in Bucharest, of which only 6816 were included in a printed catalog of caves in Romania. Using data from various publications, 8128 caves are compiled in an online database at speologie.org (Onac and Goran 2019). |

CBPW 2021 was designed as an interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary scientific event focusing on novel investigations of climate and environmental changes in the CBR since the Last Glacial Maximum. The contributions approached a diverse range of topics which included, most notably: single and multi-proxy paleoclimate reconstructions based on peatbog and lacustrine sediment archives; reconstructions of characteristics and extents of glaciers and glacial landforms in the Carpathian and Balkan ranges; cave records as indicators of climate variability; vegetation history, past fire regimes and their drivers; dendrochronological investigations; assessments of past and present human impacts and pollution history; studies of geoarchaeology, geohistory and landscape archaeology; land use/landcover changes in relation to climate variability; and modeling techniques for climate and environmental variability. Additionally, CBPW 2021 included a session dedicated to sustainable forest management in the CBR in the context of adaptation to climate change and the necessity for continued provisioning of the forest ecosystem services communities depend upon, which included the topics of forest ecology, science, and management relating to global change (e.g. climate disruption, alteration of disturbance regimes, and increasing pressure for exploitable natural resources).

The workshop was attended by about 50 participants from Romania, Ukraine, the Republic of Moldova, Russia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Poland, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, France, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, Ghana, the USA, Brazil, and Colombia. Both the variety of scientific approaches introduced by the researchers and the diversity of the participants in terms of scientific backgrounds and level of research experience (including early-career and senior researchers and academics) were noteworthy. Organizers were fully committed to ensuring that CBPW 2021 offered equitable opportunities for participation in terms of gender, ethnicity, and age to all scientists who were interested in attending.

In the current pandemic context, which has disrupted the social and networking aspects of scientific meetings worldwide, this hybrid event was able to provide a space for sharing knowledge and boosting collaboration for future research, as well as for yielding high quality scientific content suitable for publishing a special volume of a Web of Science journal dedicated to advancing paleoscience in the Carpathian-Balkan region.

affiliationS

1Department of Geography, University of Suceava, Romania

2Geoconcept Association of Applied Geography, Carlibaba (Fluturica), Suceava, Romania

3Faculty of Geography, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iaşi, Romania

contact

Marcel Mindrescu: mindrescu atlas.usv.ro

atlas.usv.ro

references

Bădescu B, Tîrlă L (2020) The karst map of Romania. Ed Pro Marketing, 51 pp

Onac BP, Goran C (2019) In: Ponta GML, Onac BP (Eds) Cave and Karst Systems of Romania. Springer, 21-35

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

Better understanding the ice-sheet and solid-Earth processes that drive paleo sea-level change remains an important topic discussed at the 2021 joint PALSEA-SERCE virtual meeting (PALSEA: PALeo constraints on SEA level rise, pastglobalchanges.org/palsea; SERCE: Solid Earth Response and influence on Cryospheric Evolution, scar.org/science/serce/serce). The meeting (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/26991) spanned four half-days and included 29 talks, 24 posters, and several group discussions. Over 110 participants joined the meeting and engaged in written and live conversations.

Most presentations revolved around two main themes: (1) developing and improving numerical models investigating the interactions between ice-sheet dynamics and solid-Earth deformation; and (2) providing new observations on paleo sea levels, ice-sheet retreat, and ongoing Earth deformation. From the modeling perspective, an important theme was that climate- and boundary-condition uncertainties remain large, requiring a move towards large ensemble simulations and machine-learning approaches. Within the observational science, new data were presented on important locations across the globe including Greenland, Northern Europe, Micronesia, the Bahamas, Antarctica, and the USA. These new observations and careful compilations build the foundation for improving models of solid Earth deformation (glacial isostatic adjustment, GIA) and our understanding of past ice-sheet change.

In addition to paleo observations, speakers presented geodetic observations related to modern melt loss. One issue repeatedly mentioned was the uncertain future of geodetic observations from Antarctica, which are instrumental in understanding ice-mass loss and solid Earth structure. The Polenet stations (Fig. 1), supported to date by the US National Science Foundation, are at risk of being decommissioned in the near future. These geodetic observations are instrumental to this community, and a community effort to demonstrate the value of keeping these stations running, as well as a formulation of new science goals, is needed.

|

Figure 1: Erik Kendrick (right) installing the GPS monument at Gould Knoll (GLDK) on Thurston Island in the Amundsen Sea. Jeff Amantea (left) looks towards the Twin Otter and broadband seismic station that is part of the POLENET/A-NET project (polenet.org) (photo credit: Terry Wilson). |

As the observations increasingly improve, models of GIA used to fit them, continue to evolve as well. GIA models often assume that solid-Earth structure (most importantly viscosity) only varies with depth, which allows for fast computations and the ability to thoroughly explore trade-offs and uncertainty. While these models continue to have merit, more complex models are increasingly employed and possibly even required by the observational record. The computational cost of these models hinders data assimilation through large ensemble runs; however, adjoint techniques might provide a path forward to efficiently constrain 3D viscosity with sea-level data. In addition to lateral variability, several speakers explored the role of transient and nonlinear rheologies and demonstrated that these complexities are not only more realistic, but may also help reconcile sea-level observations on different timescales. An upcoming challenge in the community will be to efficiently constrain all the new parameters that emerge from these models ranging from grain-size and temperature, to water content and background stress. Tighter connections to the mineral physics and geodynamic community are critical in achieving this goal.

As GIA models evolve, we need to develop standards for benchmarking and output sharing. In the past, the PALSEA community has produced community papers surrounding data compilations (Düsterhus et al. 2016) and research priorities (Capron et al. 2019). A new community effort should tackle GIA modeling standards. This could include describing and unifying modeling options, and quantifying their importance, as well as identifying a baseline set of benchmarks to be used. Additional benchmarking is needed for components related to horizontal motion and 3D viscosity structure. A community effort should develop recommendations for code and output sharing, including standardized output formats.

We thank all the participants who engaged in this workshop and the supporting organizations: PAGES, the International Union for Quaternary Research (INQUA), the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), and Columbia University.

affiliationS

1Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA

2Department of Earth Science, University of California, Santa Barbara, USA

contact

Jacqueline Austermann: jackya ldeo.columbia.edu

ldeo.columbia.edu

references

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

Mimmi Oksman![]() 1, A.B. Kvorning

1, A.B. Kvorning![]() 1, T. Luostarinen

1, T. Luostarinen![]() 2, K. Weckström

2, K. Weckström![]() 1,2, S. Ribeiro

1,2, S. Ribeiro![]() 1, A.J. Pieńkowski

1, A.J. Pieńkowski![]() 3,4 and M. Heikkilä

3,4 and M. Heikkilä![]() 2

2

1st ACME workshop, Hanko, Finland, 25-27 October 2021

Arctic coastal ecosystems, vital for both Arctic species and people, are facing marked changes due to impacts of recent climate warming. To contextualize current changes, and to better anticipate future trends, long-term reference ecological data are needed. Marine sedimentary proxies can elucidate past ecosystems, and are widely used as tools to reconstruct past conditions. However, these tools need to be robust and reliable to ensure accurate estimations of ecological changes in nearshore Arctic ecosystems. Our present understanding and calibration of Arctic marine proxies stems predominantly from open ocean settings. Therefore, more work is needed to assess, refine, and develop marine proxies, including: benchmarking and harmonizing techniques and protocols; understanding proxy formation and behavior; and quality controlling available datasets.

In October 2021, the working group Arctic Cryosphere Change and Coastal Marine Ecosystems (ACME; pastglobalchanges.org/acme) held its first workshop, with a total of 22 participants joining either physically in Finland (Tvärminne research station) or online (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/26994). The workshop aimed to evaluate the applicability of marine sedimentary proxies commonly used for paleoreconstructions in Arctic nearshore environments, and to establish community-defined criteria for database entries. From October to November 2019, ACME conducted a survey to inform this workshop, collecting perspectives on the current state and future directions of Arctic coastal paleoceanography in order to: (1) outline priority research questions and directions; and (2) provide an overview of spatial, methodological, and ecological knowledge gaps.

The two-day meeting began with discussing results of the survey, which included five open questions and 22 multiple choice questions within the scope of three themes: status of proxy understanding in Arctic marine/coastal environments; data handling and statistical practices; and study design and community integrity. While many responses demonstrated satisfaction with present practices, a major proportion of respondents identified knowledge gaps and a need for methodological development (Fig. 1).

|

|

Figure 1: The first ACME workshop focused on improving our understanding and usage of Arctic paleoenvironmental proxies (image credit: Anna Pienkowski, Kaarina Weckström, and Maija Heikkilä). |

The remainder of the meeting focused on discussing best practices, metadata requirements, and main knowledge gaps within proxy-specific working groups: diatoms, dinoflagellate cysts, foraminifera, radiolaria, silicoflagellates, organic and stable-isotope geochemistry, highly branched isoprenoid lipids (HBIs), and sedimentary DNA. Throughout the workshop, answers to the question "What holds the most potential in our field?" were collected using an interactive vision board. The outcome from this exercise was discussed as a final activity of the workshop.

Suggestions for "best practices" identified by each proxy group encompassed all steps from sampling design and sample collection, through sample handling and laboratory analyses, to data analysis and interpretation. While several recommendations were similar across groups (sampling design, collection), some proxy-specific recommendations were proposed regarding sample handling (storage conditions, processing prior to analysis); laboratory analyses (protocols, counting methods); and data interpretation (e.g. aspects affecting proxy formation, ecological knowledge). Based on the suggested best practices, groups drafted recommendations on the most important information to be included as metadata in the planned ACME database, or other openly available data repositories.

During the discussions, participants identified key proxy-specific knowledge gaps, including: microfossil species ecologies and taxonomy; microfossil and biomarker preservation; source- and environment-specific biomarker production; and limited reference libraries for sedimentary ancient DNA. One of the most important gaps indicated by the diatom and foraminifera groups was the lack of unified, openly available modern Arctic reference datasets. Open science/open data was highlighted as holding the most promise in the field. Proxy-specific groups brought forward the need for unified analytical protocols and laboratory intercalibration studies. Multidisciplinary collaboration and multiproxy approaches were emphasized. Advancing our ecological understanding, identifying tipping points in the Earth system, multidimensional reconstructions, unraveling biodiversity trends and ecosystem networks, and improving predictive models by proxy–data assimilation were listed among the items holding the most potential.

affiliationS

1Department of Glaciology and Climate, Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Copenhagen, Denmark

2Ecosystems and Environment Research Programme, University of Helsinki, Finland

3Institute of Geology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland

4Department of Arctic Geology, University Centre in Svalbard, Longyearbyen, Norway

contact

Mimmi Oksman: mio geus.dk

geus.dk

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

Heather L. Ford1, S. Sosdian2, E. McClymont3, S.L. Ho4, S. Modestou5, N. Burls6 and A. Dolan7

|

|

Figure 1: Blue Clay Formation of Malta at Ras-il-Pellegrin from the middle Miocene (Badger et al. 2013) (photo credit: Marcus Badger). |

Reconstructions of past major transitions and warm climate states are critical for evaluating future climate projections under high greenhouse gas forcing. This working group aims to build on the success of the PAGES working group Pliocene climate variability over glacial-interglacial timescales (PlioVAR; pastglobalchanges.org/pliovar) to include the Miocene and form PlioMioVAR (pastglobalchanges.org/pliomiovar).

For decades the mid-Pliocene warm period has been a data-model comparison target (United States Geological Survery PRISM, PlioVAR, and Pliocene Model Intercomparison Project (PlioMIP); Haywood et el. 2020). During the mid-Pliocene warm period (∼3.2 Myr BP), global temperatures are estimated to have been ∼2.3°C warmer than today (McClymont et al. 2020) and atmospheric CO2 is estimated at ∼394–330 ppm (de la Vega et al. 2020). However, as modern atmospheric concentrations rise above 410 ppm, it is increasingly necessary to expand our efforts to other periods of sustained warmth.

Expanding interest in Miocene research (∼23.03 to 5.33 Myr BP; Lawrence et al. 2021; Burls et al. 2021) includes the mid-Miocene Climate Optimum which is another globally warm equilibrium climate state for data–model comparisons when atmospheric CO2 was higher than today (∼600 ppm; Sosdian et al. 2018). Additionally, the ice-sheet expansion and cooling of the mid-Miocene Climate Transition presents another opportunity to study threshold climate changes and forcing mechanisms, much like the Northern Hemisphere glaciation during the Pliocene, a PlioVAR scientific objective.

Launching the PlioMioVAR working group will provide a framework for sharing best practices in community-wide engagement, database building and data-model comparison.

Scientific goals and objectives

The PlioMioVAR working group has three main goals. The first is to maintain the existing PlioVAR database and expand to the Miocene by synthesizing climate records and including age-model quality metadata. This will help identify the Miocene target for data-model comparison (likely the Miocene Climate Optimum) and identify gaps in our current Miocene paleoclimate records (temporal resolution, spatial coverage, proxy confidence). The second is to explore new data-model comparison studies to characterize climate variability including transient model simulations and coupled models with biogeochemistry. The third is to compare the long-term evolution of Pliocene and Miocene climate and consider forcing mechanisms like tectonic gateways or CO2.

Planned workshops

EGU Galileo Conference "The warm Pliocene: Bridging the geological data and modeling communities", with funding from UKIODP and PAGES, is scheduled in August 2022. In addition to presenting the major achievements of PlioVAR, PlioMIP and the rest of the Pliocene community, this workshop will include discussions on launching PlioMIP3, developing synergy between the PlioMIP3 and PlioMioVAR community and strategizing community engagement with the IODP 2050 Science Framework. The conference will take place in Leeds, UK, from 23 to 26 August 2022 with in-person and virtual options (egu-galileo.eu/gc10-pliocene).

The Miocene temperature community has plans to hold a workshop in the fall of 2022. The workshop would bring together data collectors from various proxy communities to synthesize temperature data. In addition to examining best approaches to a global temperature reconstruction and exploring regional and global temperature patterns, another goal of this workshop is to develop a plan for providing useful output for the modeling community.

Visit the PlioMioVAR website at pastglobalchanges.org/pliomiovar and sign up to our mailing list to keep up to date with our activities. Updates on complimentary Pliocene and Miocene modeling efforts can be found at geology.er.usgs.gov/egpsc/prism/7_pliomip2.html and deepmip.org/deepmip-miocene, respectively.

affiliationS

1Queen Mary University of London, UK

2Cardiff University, UK

3Durham University, UK

4National Taiwan University, Taiwan

5Northumbria University, UK

6George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, USA

7Leeds University, UK

contact

Heather L. Ford: h.ford qmul.ac.uk

qmul.ac.uk

references

Badger et al. (2013) Paleoceanogr Paleoclimatol 28: 42-53

Burls NJ et al. (2021) Paleoceanogr Paleoclimatol 36: e2020PA004054

de la Vega E et al. (2020) Sci Rep 10: 11002

Haywood AM et al. (2020) Clim Past 16: 2095-2123

Lawrence KT et al. (2021) Eos 102, doi:10.1029/2021EO210528

Publications

PAGES Magazine articles

2022

Past Global Changes Magazine

Konstantina Agiadi1, B.A. Caswell2, M. Bas3, P. Holm4 and J.A. Lueders-Dumont5

Climate and human activities altered marine ecosystems for thousands of years before industrialization, changing the structure and dynamics of marine communities, and the distribution, ecology, and physiology of marine organisms (e.g. Jackson 2001; Engelhard et al. 2016). However, disentangling these impacts from those of natural climate variability (Kowalewski et al. 2015; Agiadi et al. 2018), remains a challenge. Pre-industrial baselines are, therefore, necessary to understand the true magnitude and rate of change induced by modern anthropogenic activities, including climate change.

Q-MARE (pastglobalchanges.org/q-mare) brings together scientists from vastly different disciplines, including historians, archaeologists, paleontologists, and ecologists, to explore the impacts of climate and human activities on the environment during the pre-industrial era. Time series from scientific monitoring postdate the industrial revolution. Therefore, our working group relies on a variety of tools for reconstructing patterns of biodiversity loss and ecosystem resilience. Moreover, we aim to provide guidelines for the integration of multidisciplinary observation data and proxy-based reconstructions with dynamic ecosystem models.

|

Figure 1: Raking for Holocene shells in the Bahamas (photo credit: Tobias Grun, University of Florida). |

Scientific goals and objectives

How did climate and human activities affect marine ecosystems in the pre-industrial Holocene and the Pleistocene? Fossil and death assemblages provide data on both exploited and unexploited species. However, these archives have been a largely untapped resource for disentangling the relative contributions of climate and human activities on biota. Disproportionate changes in abundance and/or disappearances of exploited species reflect human impacts (Dillon et al. 2021), whereas climatic changes show effects across species (Albano et al. 2021). Such selective changes are visible in the stratigraphic record and can be interpreted along with paleoclimatic, archaeological, and historical records.

When did humans start having a significant impact on the marine environment? Historical, archaeological, and sedimentary records will be combined to construct a database that will then be used to identify some of the first human impacts and their causes. In addition, pivotal studies on the importance of quantifying ecological baselines will be revisited, considering new knowledge on the timing of the first human settlements and medium-to-large-scale marine resource exploitation in different regions, and their possible impacts on the natural environment (Engelhard et al. 2016; Holm et al. 2022).

How can data from different sources be combined to inform environmental conservation targets and model marine ecosystems? We aim to provide clear solutions to the methodological issues and guidelines for accessing, processing, and analyzing data derived from different sources (paleontological, archaeological, and historical) and integrating them into dynamic ecosystem models, such as dynamic food-web models, for disentangling human and climate impacts.

Visit the Q-MARE website at pastglobalchanges.org/q-mare and sign up to our mailing list to receive news and updates on our activities.

Upcoming activities

The first Q-MARE meeting was held 17–19 January 2022 online (pastglobalchanges.org/calendar/128791). Our next events will be a workshop on "Quaternary marine ecosystems" (December 2022) and a group meeting in early 2023 (both online), an in-person stakeholder engagement meeting in late 2023, and a training workshop in 2024.

affiliationS

1Department of Palaeontology, University of Vienna, Austria

2Department of Geography, Geology, and Environment, University of Hull, UK

3Forestal Catalana, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain

4Trinity Centre for Environmental Humanities, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

5Department of Geosciences, Princeton University, USA and Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Panama

contact

Konstantina Agiadi: q.mare.wg gmail.com

gmail.com

references

Agiadi K et al. (2018) Quat Sci Rev 196: 80-99

Albano PG et al. (2021) Proc R Soc B 288: 20202469

Dillon EM et al. (2021) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 118: e2017735118

Engelhard GH et al. (2016) ICES J Mar Sci 73: 1386-1403

Holm P et al. (2022) Fish Fish 23: 54-72